John Szarkowski, a curator who almost single-handedly elevated photography’s status in the last half-century to that of a fine art, making his case in seminal writings and landmark exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, died in on Saturday in Pittsfield, Mass. He was 81.

[Quote: New York Times Obituary]

American Photography

As the New York Times points out John Szarkowski “was first to confer importance on the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand” and two of his books, “‘The Photographer’s Eye,’ (1964) and ‘Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures From the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art’ (1973), remain syllabus staples in art history programs.” Szarkowski also introduced the work by William Eggleston in the now legendary exhibition “William Eggleston’s Guide” (1976). This exhibition “was widely considered the worst of the year in photography.”

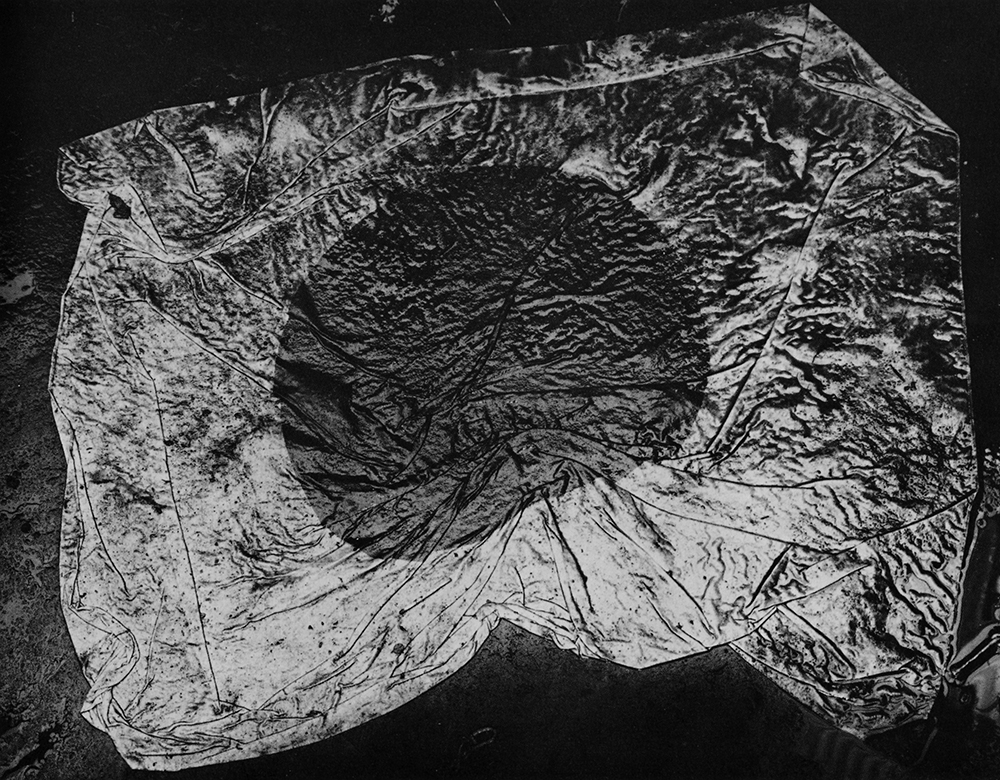

New Japanese Photography

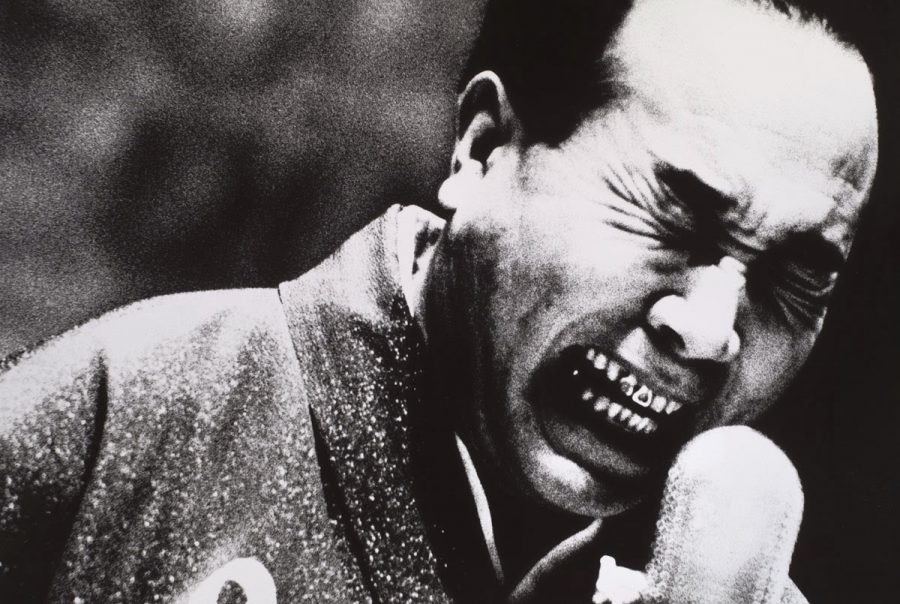

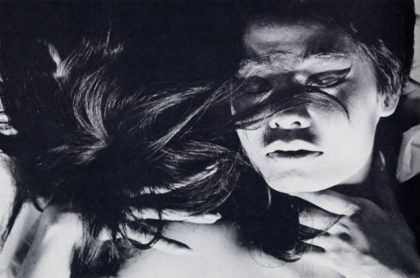

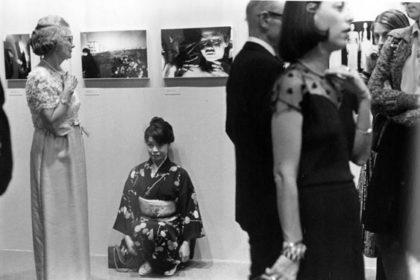

John Szarkowski left definitely his mark in the field of American photography, but not only there. In 1974 John Szarkowski organized together with Shôji Yamagishi (editor of Camera Mainichi magazine) the exhibition “New Japanese Photography”. The exhibition introduced 15 photographers, amongst them the grand masters of Japanese photography: Ken Domon, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Shomei Tomatsu, Kikuji Kawada, Masatoshi Naitoh, Tetsuya Ichimura, Hiromi Tsuchida, Masahisa Fukase, Ikko, Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama, Ryoji Akiyama, Ken Ohara, Shigeru Tamura, and Bishin Jumonji.

It was the first major exhibition about contemporary Japanese photography outside Japan ever.

Immediate Experience

Besides the excellent selection of artists and photographs, the catalog to the exhibition with two short essays by John Szarkowski and Yôji Yamagishi laid the groundwork for the reception of Japanese photography of the 1960s and 1970s.

In his essay John Szarkowski formulated within one paragraph the foundation for all later interpretations of this epoch of Japanese photography:

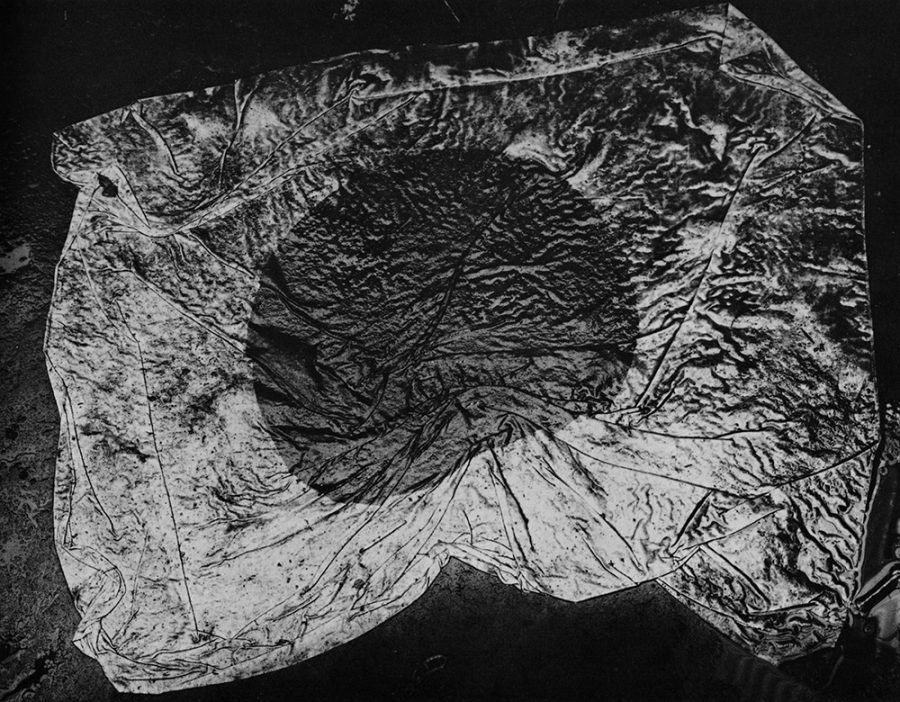

The quality most central to recent Japanese photography is its concern for the description of immediate experience: most of these picture impress us not as a comment on experience, or as a reconstruction of it into something more stable and lasting, but as an apparent surrogate for experience itself, put down with a surely intentional lack of reflection.

[Quote: John Szarkowski]

And Yôji Yamagishi described a major difference of the Japanese photographic practice of that time:

Contemporary Japanese photographers have values which seems distinct from those of the photographers of the West. They are, for example, not particularly interested in the quality of the finished print. […] Japanese photographers have only a limited opportunity to present their original prints to the public. (Nor do they have the opportunity to sell their pictures to public or private collections.) […] Japanese photographers usually complete a project in book form, joining in series a number of photographs related by a common subject, theme, or idea. The full value or impact of such work cannot be understood if individual pictures are isolated from the series for exhibitions on the walls of a museum. To do this deprives the photographs of their intended relationship to those which preceded or followed them in the series. In addition, the photographs were originally made to be reproduced in print form, in books and magazines, and not to be displayed a part of an exhibition. It is therefore almost impossible to present a precise and objective picture of the complexities of Japanese photography in an exhibition format.

[Quote: Shôji Yamagishi]

Neither Mirror nor Window

Both essays and especially the two quoted paragraphs are asking for to be commented and evaluated from today’s perspective. I just would like to note that Szarkowski and Yamagishi opened for the first time the window to another continent of photography and they established the fact that the Japanese visual artists developed a unique way of describing the world with the medium photography. A photography which was neither interested in being a mirror (“”mirrors”-pictures that mean to describe the photographer’s own sensibility”) nor a window (“”windows”-realist photos of fact, including the facts of photography seen as a system. In short, the romantic vs. the realist”), the explanation in brackets is a quote from Robert Hughe’s review on John Szarkowski’s exhibition “Mirrors and Windows” for Time Magazine (1978) but which was direct, radical, unfiltered emotional and at times raw and dirty.

An Extraordinary Anthology of Photographic Images

This exhibition belongs definitely to John Szarkowski’s landmark exhibitions and this was already asserted by N. Y. Time’s critic Hilton Kramer:

This is, by any standard, an extraordinary anthology of photographic images. […]

It is perhaps most extraordinary in the way it addresses itself to the rapid and radical changes that have overtaken Japanese life in this tumultuous period. Pictures such as Ryoji Akiyama’s “TV Frame Left in a Reclamation Area, Tokyo” (1970) and Hiromi Tuschida’s untitled photograph of a country picnic (1969) places us so firmly in the present that we can never again quite think of Japan in terms of the old romantic images.

Even more powerful – but powerful in an oddly esthetic rather than documentary fashion – are Shomei Tomatsu’s pictures of victims suffering various disease and physical disfigurements as the results of the atomic blasts that ended World War II. Yet rivaling these pictures in imaginative grotesquerie are the bizarre, erotic “inventions” of Eikoh Hose entitled “Killed by Roses” (1963), which bring a kind of cinematic freedom to the still medium.

[Quote: Hilton Kramer, New York Times, 1974]

Impact

For the curators (and collectors) of the 1970s and later the exhibition could have served as a guide book into at that time uncharted waters for to produce great shows and/or to start a leading collection of contemporary Japanese photography (of course it would have cost almost nothing to set up such a collection) – but nothing much happened in the two following decades. A reason could be that even though critics like Hilton Kramer found the exhibition extraordinary, he and others missed the focal point and real value of the show: while John Szarkowski and Shôji Yamauchi emphasized the distinction between Japanese and Western photography, Kramer’s final conclusion pointed in the opposite direction.

It will not do, I think, to try to discern a specific Japanese esthetic at work in this exhibition. What, if anything, dominates the eshetic spirit of the show is a sense of dialogue – sometimes harmonious, sometimes no – between Japanese and Western sensibilities.

[Quote: Hilton Kramer, New York Times, 1974]

There were some singular follow-ups to “New Japanese Photography” like the exhibition “Japan: A Self-Portrait” organized by Shôji Yamagishi for the International Center of Photography in New York (1979), but just as with the William Eggleston exhibition John Szarkowski was ahead of his time.

Wow, Japan looks in a state of dread through those images.

No kidding about the bargain price on the catalog, I found it selling for under $3 on Amazon & picked up a spotless like-new copy for $35. Thanks for the pointer!

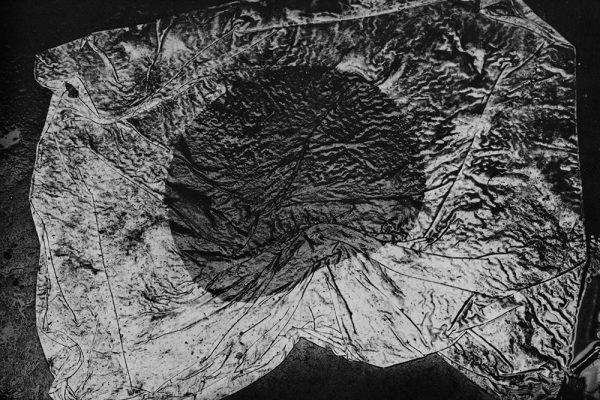

This flag of Japan is really amazing… Japanese people are just full of creativities…

Wonder how this JP flag picture was taken~

This is very powerful photography.

Some of it reminds me of 20’s and 30’s era photography, very beautiful.

Wont you know that the earliest magic is all the way from japan.it involves some illusions like their state of photography in their contry ,this picture shows that Japanese photography is a worldclass standards that leads their success.

[…] en la fotografía moderna no resulta para nada desdeñable, sino todo lo contrario. Además, puso en valor en occidente a la fotografía japonesa, y se atrevió a introducir a la fotografía en color, hasta entonces denostada, como vehículo […]