Previously I had posted an interview I did with Mariko Takeuchi on Japanese photography, this time I am posting an interview the Berlin publisher Roland Angst did with me on the Japanese photographer Issei Suda for the first Western monograph in the artist.

Suda is slowly becoming more popular in the West[1]At GALERIE PRISKA PASQUER we introduced Issei Suda’s work with two solo exhibitions in 2009 and 2013 and frequent presentations at fairs like Paris Photo, AIPAD New York and … Continue reading with his distinct but mysterious 1970s work as a kind of antithesis to the raw energy of the Provoke photography.

Issei Suda, a Master of Japanese Photography | Interview by Roland Angst with Ferdinand Brueggemann

Published in: “Issei Suda – The Work of a Lifetime – Photographs 1968 – 2006“, Only Photography, Berlin, 2011

RA: Is it correct to say that Suda succeeds – despite the strong influence of Japanese history and tradition on his perceptions and his choice of motifs – in creating a modern image of Japan, albeit one that is more classic than provocative, as in the case of the Provoke Group?

fb: In Suda’s case, we see things coinciding, and this is always an essential factor in making Japanese art so unique: the fact that the Japanese draw from different sources. I already mentioned this in relation to the topics chosen by Japanese photographers in the 1960s and 1970s: the tense relationship between tradition and modernity: this is also a conflict in the life and work of artists from this period, and it is most radically reflected in the life of the author Yukio Mishima, who, as a representative of the avant-garde, took his own life through «sepukku», the traditional form of suicide, in 1970. Before he became a freelance photographer, Issei Suda was a theater photographer working for Shûji Terayama’s “Tenjô Sajiki” acting troupe. Terayama was one of the central figures in the Japanese avant-garde of the 1960s and had contact to a wide variety of artists from this period. Terayama worked with Tadanori Yoko’o, for example, one of the most important graphic designers in Japan (and he in turn worked with the photographer Eikô Hosoe). There are also a number of early photographs of Daidô Moriyama taken within the context of this theatre troupe. Hence, there was an extremely lively and intensive network within the Japanese avant-garde that served to connect all of the arts during this period.

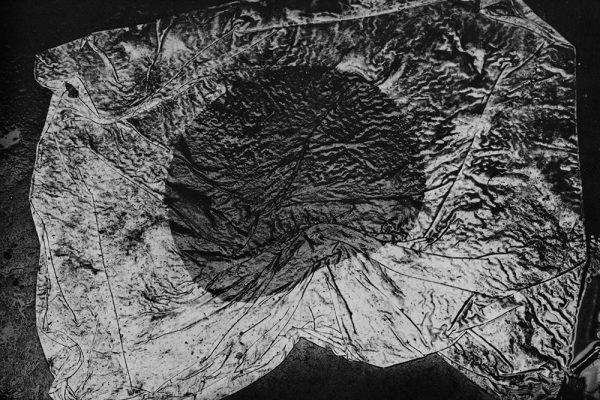

Returning to the confrontation between tradition and modernity in Issei Suda’s work: after the period he spent as a theater photographer, it was not surprising that his first book drew its title from a work on the theory of acting. Yet it is also important to note that he chose a title from the Japanese Middle Ages, the title of a book by one of the founders of the Japanese theater tradition.

His choice of this title is a reference to the fact that Issei Suda apparently sees reality with two different eyes. He bears witness to the changes in Japan, to its having been propelled into modernity, yet refers to an aesthetic style that is centuries old; and in doing so, he makes use of a visual medium that was, in turn, introduced to Japan from the West. This, in my opinion, is what is so special about Suda: this tension between the ordinary and the extraordinary, between tradition and modernity. This precise observation and description, whereby the unusual tension in these images, which always embody a sense of mystery, is what makes the work that Suda was doing so different from that of other artists in this period. The Provoke photographers, whose best works hit the viewer like a slap in the face, fail to demonstrate this subtlety.

RA: Was Suda integrated into the Japanese photography scene? And when was he first noticed by Japanese museums?

fb: In general, there has always been a very strong network within the photography scene in Japan. Personal contacts, magazines and exhibitions always provided a basis for a very close-knit network. One reason for this was that in the early decades photographic artists received very little support from outside of the photography scene; moreover, up until a few years ago, there was not much of a market for photography, nor were photographs discussed in magazines or newspapers outside of the photography scene. People tended to work for themselves and their colleagues within the scene, and to provide support for each other in realizing projects and staging exhibitions. Yet, in his work, Suda really seems to be original; he also denies having been influenced by others, although he was certainly, albeit unconsciously, affected by the “Kompora” movement, particularly since an intense discourse regarding the medium of photography was being conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, mainly in photography magazines and books by photographers.

Unlike the Provoke artists, Suda did not establish a trend in photography, although his manner of seeing sometimes seems to shine through in the work of other photographers. Regarding Suda’s presentation in Japanese museums, I was surprised to realize that he has never had a solo exhibition in a Japanese museum, although his works can be found in many Japanese museum collections. Moreover, his work was first exhibited at Western institutions, such as the ICP in New York and the Forum Stadtpark in Graz. This is, on the one hand, due to historical reasons. Japanese museums did not establish photographic collections until the late 1980s or early 1990s. On the other hand, Japanese museums are very cautious about presenting Japanese artists. Quite often, Japanese artists are only appropriately recognized after they have had successful solo exhibitions in Western museums. Kusama Yayoi, the important Pop-Art artist, and Nobuyoshi Araki, as well as the current case of Rinko Kawauchi, are examples of this.

RA: Is it true that you, as the director of the Galerie Priska Pasquer, were responsible for introducing Suda in the West?

fb: I believe that the presentation of his work in our gallery marked an important step in acquainting Western collectors and curators with Issei Suda.

RA: Has Suda’s work been represented in the very few group exhibitions on Japanese photography staged in recent decades?

fb: Issei Suda’s work was shown in the important exhibition The History of Japanese Photography in Houston, Texas, in 2003. The catalogue from the exhibition can now be used as a reference work on the history of Japanese photography. It made an essential contribution to our knowledge of Japanese photography, particularly due to its in-depth research. Issei Suda’s work was also presented in earlier exhibitions. We have now largely forgotten that Japanese photography was already shown in the 1970s. There were three important exhibitions: New Japanese Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, organized by John Szarkowski in 1974; Japan: A Selfportrait at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York in 1978 – in which Suda also participated; and Neue Japanische Fotografie in Graz, in 1977. They seem to have had little effect back then. They were, unjustifiably, not recognized in the West as extraordinary moments in exhibition history.

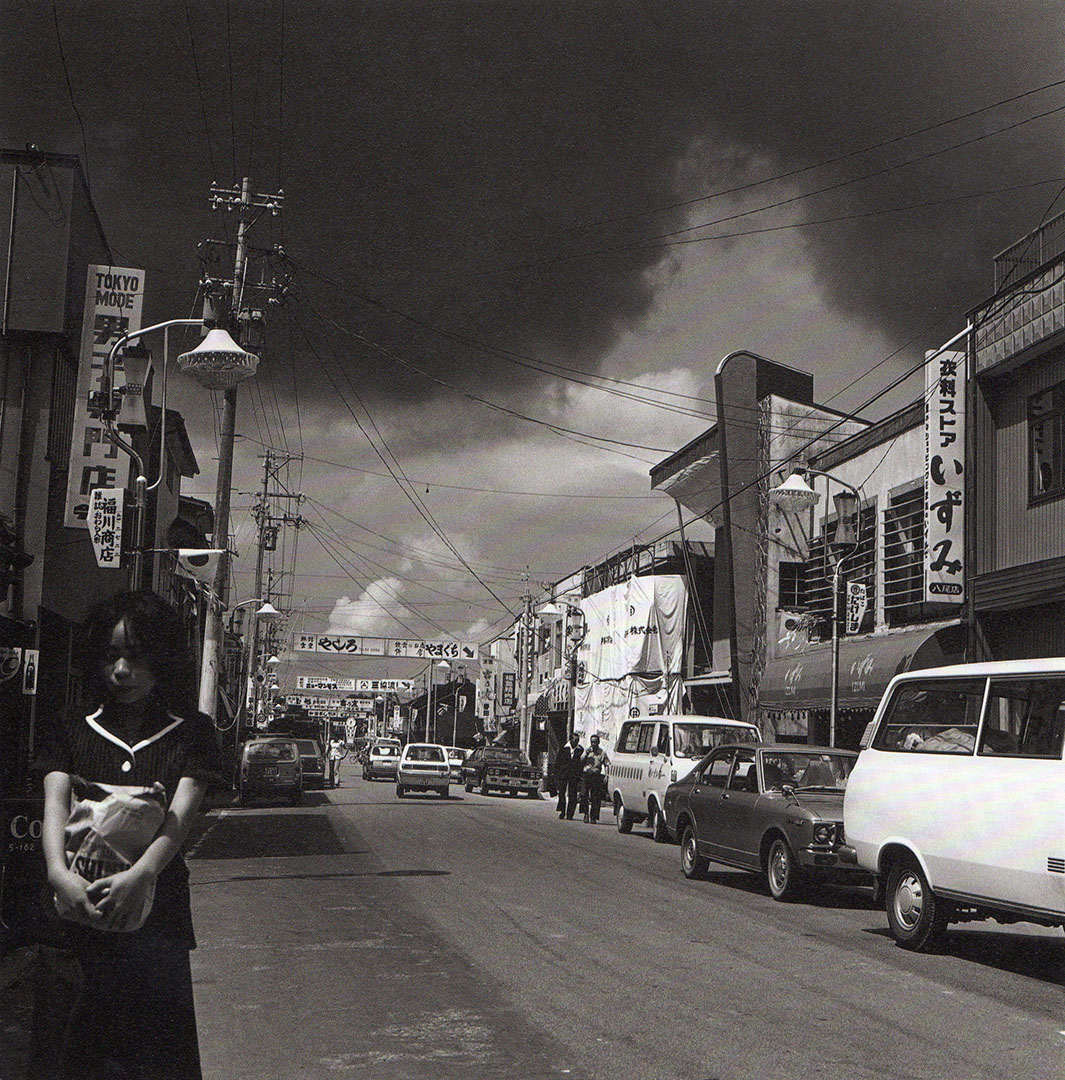

RA: As you correctly pointed out, Suda engaged with Japanese history – particularly with Nô theater. How do you assess his decision to turn to images of modern urban Japan, particularly to Street photography, within the context of his overall oeuvre?

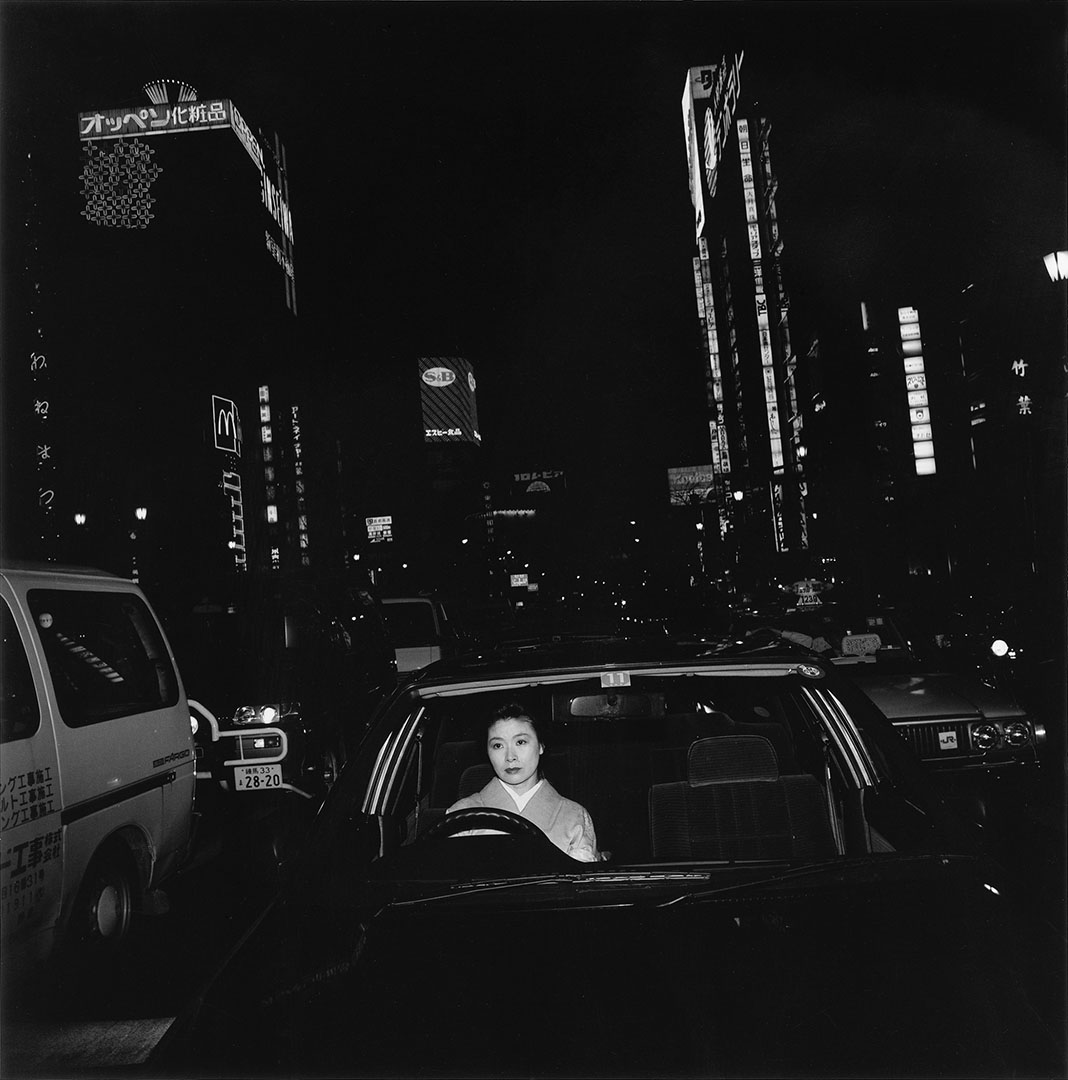

fb: Along with Fûshi kaden, I see the book Human Memory, which was created during the 1980s, as an important milestone in his work. In it you can really see a change taking place, Suda has returned to the city. He photographs everyday scenes – but not necessarily scenes from the vibrant centre of the metropolis of Tôkyô, he instead shows side streets and areas that seem more like small towns. While in Fûshi kaden Suda repeatedly showed people in groups, couples and cliques, or people celebrating, sometimes assuming exaggerated poses, one notices that many of his photographs in Human Memory depict a sense of isolation.There is still the strange tension in Suda’s images, which is based on the depiction of the unusual in everyday life – which seem, however, somehow muted. The focus is more on the scenes in which people appear as isolated individuals in an urban context.

RA: Does that mean that he is reacting to what was then a contemporary trend, one that was surely quite confusing for the more traditional and family-minded Japanese?

fb: He is indeed examining – consciously or unconsciously – a social trend that became quite pronounced in Japan in this period. The major cities – above all the Tôkyô metropolitan region, which is now inhabited by over 32 million people – exerted a tremendous attraction; people moved to the cities and were thus torn out of their village communities. In the cities, the people now appear as isolated individuals. Tôkyô’s rise, the rapid changes in the appearance of the city and the radical transformation of the social structure play a central role in the discourse in Japanese photography during this period.

RA: Ferdinand, I thank you for speaking with me.

This interview with Ferdinand Brüggemann was conducted by Roland

Angst on October 11, 2011 at the Galerie Priska Pasquer in Cologne.

References

| ↑1 | At GALERIE PRISKA PASQUER we introduced Issei Suda’s work with two solo exhibitions in 2009 and 2013 and frequent presentations at fairs like Paris Photo, AIPAD New York and Art Basel. See here: https://priskapasquer.art/issei-suda/ |

|---|