Did anybody see the exhibition Berlin – Tokyo / Tokyo – Berlin at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo or later in Berlin? I wasn’t neither able to see the exhibition in Tokyo nor at the second venue in Berlin afterwards.

The reviews in the German press were very positive (except on the contemporary part of the show), while in Japan the review at the Japan Times was quite crushing:

Berlin/Tokyo: Invitation to a car wreck

The exhibition “Tokyo-Berlin/ Berlin-Tokyo” was put together by a total of 17 curators and assistants, and looks like it. This is a dog’s breakfast of a show — although there is a lot of good art here, the total amounts to less than the sum of the parts. If there is a unifying theme, it is trepidation, the fear of putting a foot wrong.

[Quote: Monti diPietro, Japan Times]

Some better examples

While I cannot say anything about the exhibition, I found the catalogue to the exhibition very weak compared to previous exhibition catalogues about the relationship between the West and Japan. Just take for example the catalogue to a similar themed exhibition “Japan und Europa 1543-1929” which was shown in Berlin in 1993. The catalogue to “Japan und Europa 1543-1929” contains many elaborate essays and additionally detailed descriptions and comments to every piece exhibited. Or you could take the more recent exhibition catalogue “Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500 – 1800” (Victoria &Albert Museum, London 2004) which contains very insightful essays on the early encounters between the West and Japan. I have seen the show and I keep it in my mind as a very important contribution to our knowledge about the cultural exchange in the early stage of the contact between the Far East and Europe.

Below expectation

The exhibition catalogue “Berlin – Tokyo / Tokyo – Berlin” does not meet the standard of the above mentioned publications for a very simple reason: the essays are so short that they just are able to name the absolute basic facts on either the Japanese or the German art history and the exhibited art works lack any explanatory comments. Moreover the complex discourse of the two cultures, the innovations and (sometimes positive) misunderstandings of cultural transfers between Japan and Germany, the multilayered historical relationship of the two cultures is only touched superficially.

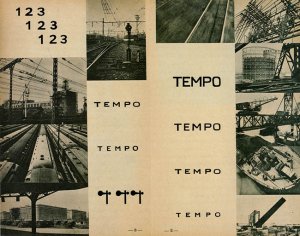

For example the essay by Kotaro Iizawa on “Japanese photography and Berlin” is way too short to discuss the extreme enthralling encounter between the German New Photography and the Japanese Avant-garde photography in Kantô and Kansai. Iizawa mentions the Japanese photographer and publisher Yônosuke Natori, but unfortunately the catalogue and the exhibition missed the chance to illustrate the importance of Natori as a vital link between Germany and Japan in regard to journalistic/documentary photography.

Some of the essays are a kind of autistic in regard to the main topic of the exhibition: the exchange between Tokyo and Berlin. Mostly the essays concentrate on the developments either in Berlin or in Tokyo, without looking at the vital relationship between the two capitals, or worse without even mentioning the other city. But the missing dialogue between Tokyo and Berlin is not the fault of Japanese and German authors like Kotaro Iizawa or Jaqueline Berndt (she writes on Manga in Tokyo). Authors like Iizawa and Berndt are well known and prolific specialists in their areas of research who know the Western _and_ the Japanese side of the cultural exchange.

But specialists like Jaqueline Berndt aside unfortunatley most of the Western researchers on Modern art have no idea what happened in Tokyo – which, to their excuse, often has a very practical reason: only in the recent years detailed information about Japanese art of the 20th century became available in Western languages. In contrary to most Western scholars all Japanese researchers and museum curators I met in Japan have a deep understanding of Western art (modern and contemporary). Actually, I too was one of the Western ignorants when I traveled to Japan in the 1990s and felt like a like a first-grader in front of the Japanese scholars – fortunately over the years several Japanese curators were very generous in taking their time to introduce me to the main aspects of Modern Japanese photography.

Asymmetry

Besides the very reduced account of a dialogue between the two capitals I also missed any reference on the entirely asymmetric relationship between the German (Western) and the Japanese art scene for most of the 20th century. In the catalogue you will find some authors writing, albeit much too short, about the important influence the German Avant-garde had on Japanese art (Dada, Bauhaus, New Vision, e.g.), but I did not find any discussion of the cultural transfer of Avant-garde art from Tokyo in the direction of Berlin.

As far as I know the cultural transfer from Tokyo to Berlin of modern and contemporary art almost never took place – very much in contrary to contrast to pre-modern art and culture!). [Please correct me if I am wrong, I would love to learn about contrary evidence!]. In my opinion it would be very interesting to discuss the question why the transfer from Tokyo to Berlin did not happen.

This discussion would need to include the question how the modern (and until the 1980s contemporary) art movements in the ‘periphery’ (like Japan) were perceived by Western Avant-guarde artists and critics. And it would also have to include the discourse about the self-conception and self-definition of the Western Avant-garde and its differentiation from the Japanese Avant-garde. Because obviously the Japanese Modernism didn’t fit at all in concept of the Avant-guarde in the eyes of the Western critics and artists.

Of course, there was the famous Japonism movement:

From the 1860s, ukiyo-e, Japanese wood-block prints, became a source of inspiration for many European impressionist painters in France and the rest of the West, and eventually for Art Nouveau and Cubism. Artists were especially affected by the lack of perspective and shadow, the flat areas of strong color, the compositional freedom in placing the subject off-centre, with mostly low diagonal axes to the background.

[Quote: Wikipedia]

But it seems that in the 20th century the West and the Western artists were exclusively interested in premodern Japan, its feudal culture, the old temples and shrines, the Zen aesthetics, Hiroshige’s wood cuts, e.g.. This romantic vision and version of Japan, which excluded the development of the modern Japanese society and culture completely, shaped the view of even the most avantgardist artists.

Bruno Taut: “I love Japanese Culture” – Really?

A graphic illustration of the above noted asymmetry is to be found in one of the most prominent representative of the German- Japanese cultural exchange: the architect Bruno Taut. Taut fled 1933 via Switzerland to Japan. In 1934 he wrote the highly influential book “Nippon seen through European Eyes”, which soon became part of the curriculum at Japanese schools. Three years later, 1937, Taut published his second book on Japanese culture: “Houses and People of Japan”. And in 1939, after Taut’s death, a collection of his essays was published in Japan: “The rediscovery of the Japanese beauty”. This posthumous anthology became a kind of a bestseller in Japan and reached an edition of around 400.000 until today.

In his writings Bruno Taut was in search for the “pure” (which means traditional) Japanese aesthetics and architecture. But he despised anything modern in Japan.

The press release of the Mori Art Museum to the exhibition “Berlin – Tokyo / Tokyo – Berlin” quotes Bruno Taut’s famous words “I love Japanese Culture” as evidence for the love of the Germans for Japanese culture.[1]A calligraphy by Bruno Taut of “I love Japanese Culture” can still be found as an inscription on a memorial stone in Takasaki, where Taut lived.

If the author of the press release would have read Bruno Taut’s book “Houses and People of Japan”, he would have found the following sentence, which contradicts Taut’s renowned declaration of love (my translation from the German edition of the book):

“Tokyo and its main shopping street, Ginza! What was before noise for the eyes became a blare. I, the sensible one, overcame a terrible depression; I did not talk anymore and I already deeply regretted my travel to Japan. For to see such ugliness I did this exhausting trip […]?

[Quote: Bruno Taut]

Diminishing Influence

In regard to the German influence on Japan, it diminished almost completely after WW II, except for a short intermezzo of the German so called Subjective Photography. In the 1950s the USA took over as the leading source of contemporary culture. The “Berlin – Tokyo” catalogue (unintentionally?) reflects the diminished artistic dialogue between Germany and Japan after 1945, there is almost no visible interaction between contemporary Japanese and German art works.

Color movie of Tokyo 1935

But, why today this post on the exhibition “Berlin – Tokyo/ Tokyo – Berlin” after the exhibition has ended many months ago? Because I am a huge fan of Modern Japanese culture, I appreciate the photographs of Japanese Shinkô Shashin (New Photography), and I am fascinated by the energetic life in modern Tokyo like it is decribed in the novel The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa by Yasunari Kawabata (1930). But first and foremost because I just found a color movie of Tokyo from 1935 which shows how modern Tokyo was during that time – a Tokyo completely unknown and completely neglected by the German (Western) Avant-garde for many decades.

Tokyo, 1935 (Shôwa 10) – [without sound]

The video shows the most modern areas of Tokyo, the main shopping district, Ginza, as well as the main entertainment district, Asakusa, of that time, and other places and like Marunouchi. Also it includes the famous “Imperial Hotel” by Frank Lloyd Wright, which was destroyed in 1968.

PS: The photographs except the one from Kôyô Kageyama are not from the “Berlin – Tokyo” exhibiton. The exhibition just had less than a dozend Modern photographs. (-_-)

References

| ↑1 | A calligraphy by Bruno Taut of “I love Japanese Culture” can still be found as an inscription on a memorial stone in Takasaki, where Taut lived. |

|---|

I saw the exhibition in Berlin but didn’t get the catalog.

Not an art professional, I found it really interesting, because it revealed ties I didn’t know about. The mutual influence was very obvious, when walking in to a room.

The video you show is amazing

salut

I have seen it. And it was not that good. It was certainly interesting to see the ties between the two cities. But it missed a lot of historical context, and perspectives on the influences. The catalog is better than the exhibition for the context and cultural background.

Wonderful stuff.

I saw the exhibit, but like most of the exhibits at the big new Japan galleries, it was too expansive and exhaustive for me to digest. I think there is something to be said for using your empty space. In my opinion, the Hiroshi Sugimoto exhibit is a great model for Mori exhibitions.

I agree with Karl as well.

I have not seen the exhibition but just want to add some arguements to this article.

Mainly traditional cultural aspects were perceived by modern western artists because Japan was in isolation before (edo era) and almost no japanese knowledge was given to the west. Of course there was a lack of japanese knowledge in Europe and US. Western nations started popularizing their culture all over the world contrary to the more-or-less isolated japan during these years.

While during the Meiji-Era western countries were focussed on modern national expansion, competing against each other with new technologies (media), Japan had to build a nation, increasing it’s military powers to protect from the rising western nations. Although Japan was expanding it’s borders in the Taisho-era (1912-1926), it was far away from taking it’s culture to the other side of earth as much as western countries were doing.

In advertising terms i would say, that japan was rather forcing a local advertising than the international campaigns of the west.

So in a summary the exchange of cultural elements of Japan and of the West was greatly unbalanced. Basically in the west due to the lack of japanese knowledge there was a demand for the last hundreds of years in traditional japanese arts’ n culture, but there was no demand in modern japanese culture yet. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve over.

Eventually it is the wrong way to say that western artists have been neglecting the modern Japan or Tokyo in the pre war years. Japan didn’t do much for getting better known internationally and the west wasn’t interested so much into something that was rather unknown.

Even today Japan still persists generally as a country that sucks up loads of international influence but doesn’t manage to spit out own creations over it’s own borders as much as western countries do, although it has the power to do that.

Indeed the situation is getting better, but Japan could do so much more and it’s really worth it. Of course the west could show more interest, but you cannot create an accusation of that.

Regarding Bruno Traut i wouldn’t question his love for Japan just because he gets into a depression. His ambitions are pretty much obvious. Love and hate are close together.

Beautiful images. Surreal in a way.

Very inspiring exhibition

All this sounds very self absorbed and pretencious talk to me.

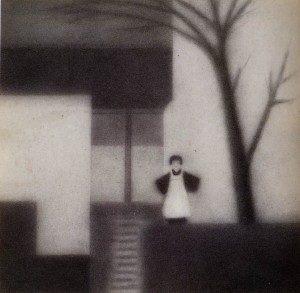

I am in love with the above image “Jun Watanabe: «Winter», 1926”, does anyone know where I can find some more examples of Jun’s work on the internet or in print? There is almost nothing on the internet that I can find aside from the currant Jun Watanabe who does graphics and illustration, very well by the way!

This is an amazing blog and I congratulate its creator. I often visit for visual references to my photographic studies and am always inspired, thankyou!

Japanese is known for their huge buildings ,it consist of both old and the modern architechture of the Japanese times,It is said that their architecture is .their strenhts.

Japanese are known for their huge and as high as the bird can flew.the japanese architecture is one of the best architecture in the world.there are several thuought that it is similar to the ancient pyramid .

One of the giant are in the continent of asia,particularly in Japan.it is known as the Tokyo tower in Tokyo,Japan,for me its the highest tower i’ve ever see i my whole lyfe and it is the one with the las vegas look alike tower,with the marching ants light with colorful schemes.

When it comes to the explosives this country is the biggest manufacturer of explosives,bombs and some deadly riffles,but this country has the most brutal way of getting in the <a href=”http://www.tokyo-forum.comexplosive materials,you know what i’m talking Japan,the most powerful country during the World WarII.