In 1966 Yutaka Takanashi published a 36 pages long spread with 43 photographs introducing his new series titled “Tokyo-jin”, a title which is usually translated as “Tokyoites” or “People of Tokyo”. The series was published in the magazine Camera Mainichi – a photo magazine which was essential documenting contemporary currents in the Japanese photography scene.(Camera Mainichi, 1966, no. 1. In the magazine the title “Tokyo-jin” was translated as “Tokyo Man”. The editor of Camera Mainichi, Shôji Yamagishi, co-curated in 1974 the seminal exhibition on Japanese photography at the MOMA, see the post on John Szarkowski, 2007.)

Photographed 1964-65 “Tokyo-jin” concentrates on the inhabitants of the megacity Tokyo. At that time Tokyo had overcome the severe destructions of World War II and new centres for consumption, mass- and avant-garde culture had emerged, now mainly concentrated in Shinjuku and Shibuya.(Before WWII Ginza and Asakusa were the heart of the avant-garde culture and Western-influenced modernity. You can find a colour video from 1935 on Ginza and Asakusa in a 2007 post. Today Asakusa is seen as representing the ‘old’ Tokyo. See for example my post on Hiroh Kikai from 2006.) Takanashi’s series shows people in public spaces, in the streets, at department stores, commuting to work – like the fantastic image of an overcrowded subway train -, or spending leisure time together.

Frequently the images contain more or less subtle hints on the radical changes the Japanese economy, society and culture underwent since the end of WWII. Takanashi depicts the Salarymen in their business suits and female shop clerks in company uniforms, who were dominating the centre of Tokyo. These Tokyoites were part of the middle class whose expanding income set the base of the expanding consumer culture. And Takanashi shows its most visible sign: young middle-class families in their first cars.

But Takanashi’s outlook at the Tokyoties isn’t just a simple appreciation of contemporary life in a megacity. Often people seem to be isolated, standing alone in the street or among the masses. And quite often Takanashi shows remnants of the traditional culture which became more and more invisible while the symbols of the American way of life and its leading brands became an essential part of the visual culture in Japan: A child with a Ray-Ban sunglasses in front of a temple and or the coca cola logo on the back of the shirt of a baseball player.

All together the flow of the images constructs a multi-layered, complex narration of a city on the move, oscillating between progress and tradition, between local habits and an increasingly internationalized consumer culture.

The “Tokyo-jin” series was very well received in the Japanese photography scene, albeit the presentation in Camera Mainichi magazine must have been looked upon as unsatisfactory: even though the magazine wasn’t of large size, 3-4 images were put on a double page. The consequence of the cramped layout was, that for the reader of the magazine the real quality of the images was only vaguely perceptible.

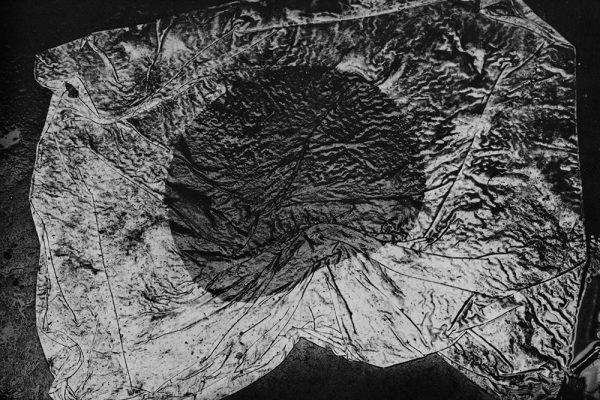

The hope that this series would later receive an adequate publication was disappointed when Takanashi published it eight years later as part of his two-volume book “Toshi-e” (Towards the City). In “Toshi-e” the “Tokyo-jin” series was again printed in a small size publication, this time roughly printed on cheapish, yellow tinted paper – but it became part of one the most impressive photobooks of the 20th century.

“(Tokyo-jin) was considered Takanashi’s representative work and an important contribution to contemporary Japanese photography. Its publication in book form had been hotly anticipated since the work first appeared in the January 1966 issue of Camera Mainichi. (…) When “Towards the City” was eventually published in 1974, buyers were befuddled and disappointed to find “People of Tokyo” treated like a mere supplement.

[Quote: Rûyichi Kaneko(Kaneko, Ryûichi, in: Japanese Photobooks of the 1060s and ’70s. New York 2010, p. 170)]

I guess that one reason for Takanashi’s decision not to present the series in a more appropriate way was, that in the second half of the 1960s Takanashi became discontent with this kind of subjective documentary photography.

Around 1967/68 Takanashi and other photographers and critics were in search of a new approach to describing reality, they were in search of a new visual “language to come”. Therefore it wasn’t a surprise that in 1968 Yutaka Takanashi became a founding member of the ‘Provoke’ collective, a collective which during its short span of life should change the Japanese photography forever and whose impact can still be traced in Japanese photography today (and in the West as well).

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Renaud COILLIOT, Yumi Goto. Yumi Goto said: In 1966 Yutaka Takanashi published a 36 pages long spread with 43 photographs introducing his new series “Tokyo-jin” http://bit.ly/arMbzm […]

[…] o arty?cie (artyku?y w j?zyku angielskim): On Yutaka Takanashi, part I: Towards Tokyo – Japan-Photo.info Photography that Provokes – The Daily Beast The Changing Faces of Japan – Tokyo Art […]

[…] o arty?cie (artyku?y w j?zyku angielskim): On Yutaka Takanashi, part I: Towards Tokyo – Japan-Photo.info Photography that Provokes – The Daily Beast The Changing Faces of Japan – Tokyo Art […]